Contents

- Sacred Bees & Liquid Gold: The Magic of Melipona Honey in the Yucatán Peninsula

- The Bee that Doesn’t Sting—But Still Commands Respect

- How European Bees Changed the Yucatán’s Beekeeping Traditions

- Meliponiculture: An Ancient Practice Still Alive Today

- Why Melipona Honey Commands a High Price

- Valladolid: A Honey Capital Rooted in the Soul

- Beekeeping and The Maya Hinterland

- Why It All Matters

- Are You Interested in Learning More About Meliponiculture?

- What Can You Do to Support Melipona Bee Populations?

- Learn More

Sacred Bees & Liquid Gold: The Magic of Melipona Honey in the Yucatán Peninsula

Tucked within the jungles of the Yucatán Peninsula lives a quiet miracle—Xunán Kab, the “royal lady bee” of the Maya. Scientifically known as Melipona beecheii, this stingless bee has been nurtured for centuries by indigenous communities who still tend to their hives with reverence. The Maya of the Yucatan have a 3200-year-old tradition of melipona bee tending. But melipona bees offer far more than honey. They carry the weight of spiritual symbolism, environmental balance, and ancestral tradition.

The Bee that Doesn’t Sting—But Still Commands Respect

Unlike the more familiar European honeybee, Melipona beecheii doesn’t sting. The genus melipona actually consists of over 50 different species of bee. Melipona beecheii can be found in the southern Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and as far south as Costa Rica. These gentle pollinators live in hollow trees or carefully constructed wooden boxes, working collectively to produce a rare and powerful honey—one with medicinal, ceremonial, and even mystical uses. Their honey is thinner, tangier, and more acidic than conventional honey.

Melipona honey is one of the most medicinally potent honeys on the planet and is the number one ingredient in the Mayan healing remedies. It’s anti-bacterial, anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory. It’s used to treat eye infections, respiratory conditions, digestive issues, and skin ailments.

Yet for the Maya, melipona honey is not merely medicine—it’s spiritual. Ancient codices like the Madrid and the Trocortesiano document rituals in which bees served as messengers to the gods. Their honey was used in childbirth, sacred offerings, and even as currency in pre-Hispanic markets.

How European Bees Changed the Yucatán’s Beekeeping Traditions

Before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, the Maya had already developed one of the most advanced systems of beekeeping in the world. For centuries, they carefully cultivated the stingless Xunán Kab, in hollowed-out logs called jobones, using intricate methods passed down through generations.

That changed with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, who brought with them the European honeybee (Apis mellifera). These bees, unlike the stingless meliponas, produced honey in far larger quantities and were more aggressive pollinators. While useful for expanding commercial honey production, their introduction disrupted traditional practices in profound ways.

The European bees quickly became dominant, favored for their productivity and adaptability to modern hives. Over time, meliponiculture was pushed to the margins—sustained mostly by Indigenous families who continued the tradition in small, home-based apiaries.

Today, both species coexist in the Yucatán but it’s becoming rare to find the melipona bee out in the wild. The apis honeybee is bigger, more aggressive and spends more hours of foraging in the day. The melipona bee was once the major polinator of the Maya selva. Now, they’re out competed by the apis for nectar collection. This is one of the reasons their numbers have plummeted.

European bees drive large-scale honey exports, but melipona honey remains deeply tied to cultural identity, used primarily in medicine, rituals, and local barter. It’s not unusual to see rural beekeepers raising both melipona bees in traditional jobones and apis bees in modern hives. Each serves a different purpose.

Meliponiculture: An Ancient Practice Still Alive Today

The tradition of meliponiculture—the care and cultivation of stingless bees—is one of the oldest forms of beekeeping in the world. The largest producer of honey for melipona bees in Mexico is in the state of Yucatan. In Quintana Roo thoughout the Mayan Zone—Felipe Carrillo Puerto, José María Morelos, Leona Vicario just to name a few areas—families also continue to raise melipona bees using inherited methods. These practices are more than rural livelihoods—they’re acts of cultural preservation in the face of modern threats.

Despite their resilience, melipona bees are in danger. Over 80% of melipona populations in the Yucatán Peninsula have disappeared in recent decades due to deforestation, agrochemical use, and climate change. Beekeepers who work with M. beecheii in the Mayan zone in Quintana Roo, have reported a staggering 93% decrease in hives over the past 25 years. The long-term effect of the loss of these bees is not just ecological—it’s cultural. Reviving and supporting melipona beekeeping protects not just biodiversity but also ancestral knowledge nearly lost to colonization.

Why Melipona Honey Commands a High Price

Melipona honey isn’t just rare—it’s exceptionally labor-intensive to produce. Unlike the more familiar honey from European bees, which can be harvested in bulk using industrial methods, Melipona honey is gathered in small quantities from handcrafted hives, often located in forested or rural areas. The harvest is done entirely by hand, with care taken not to damage the delicate wax pots the bees build inside their nests. This delicate process can take hours, and because each colony produces only a liter or two per year, even a modest harvest represents weeks or months of patient stewardship.

Adding to its value is the fact that Melipona beekeeping is rarely scaled for commercial yield. Instead, it remains rooted in small community plots and home gardens, often maintained by families practicing methods passed down for generations. These aren’t honey factories—they’re living systems of reciprocity, where the bees are treated less as livestock and more as kin. That relationship isn’t just cultural—it translates into slower harvest cycles and smaller volumes, which naturally elevates the market value.

The honey’s high price also reflects its broader significance. Because Melipona bees are so sensitive to environmental change, their honey is a kind of ecological barometer—an indicator of clean habitats, native plants, and intact forest ecosystems. In that sense, buying Melipona honey isn’t just a transaction—it’s a form of conservation support. Consumers who seek it out are often not just paying for taste or healing properties—they’re investing in the survival of both the bees and the people who protect them.

In global and specialty markets, Melipona honey is increasingly seen as a premium product, not unlike rare wines or single-origin cacao. Its tangy flavor, medicinal uses, and story-rich origins make it particularly appealing to chefs, herbalists, and ethical consumers. Whether purchased in a glass jar at a Maya cooperative or through a boutique health shop abroad, one thing remains constant: the price tag is high—but so is the value behind it.

Efforts are now underway to protect melipona honey through an official indicación geográfica (geographical indication), which would recognize the honey as unique to the Maya zone of southeastern Mexico. Much like champagne in France or tequila in Jalisco, this designation would help ensure that the honey’s cultural and ecological roots are honored and safeguarded.

This legal recognition could empower small-scale producers by increasing the value of their product while defending it from commercial exploitation. It would also raise awareness about the bees’ role in pollinating native plants like achiote, habanero pepper, and wild orchids—plants that, without these bees, might fade from the landscape entirely.

Valladolid: A Honey Capital Rooted in the Soul

Now often called the symbolic “world capital of honey,” Valladolid has emerged as a regional epicenter for both meliponiculture and honey-based innovation. The surrounding area is home to numerous family-run apiaries and cooperatives that not only produce melipona honey but also process it into soaps, balms, syrups, and natural remedies.

The Mayan Melipona Bee Sanctuary Project is dedicated to preserving the 3,200-year tradition of Maya beekeeping by safeguarding Melipona bee populations, empowering Indigenous women as bee tenders and entrepreneurs, and establishing sustainable bee sanctuaries throughout the Yucatán. By blending ancient meliponiculture practices with contemporary training, honey production, and community-based microenterprise, the organization supports cultural continuity, ecological resilience, and gender equity—all while producing rare, medicinal honey with deep cultural roots

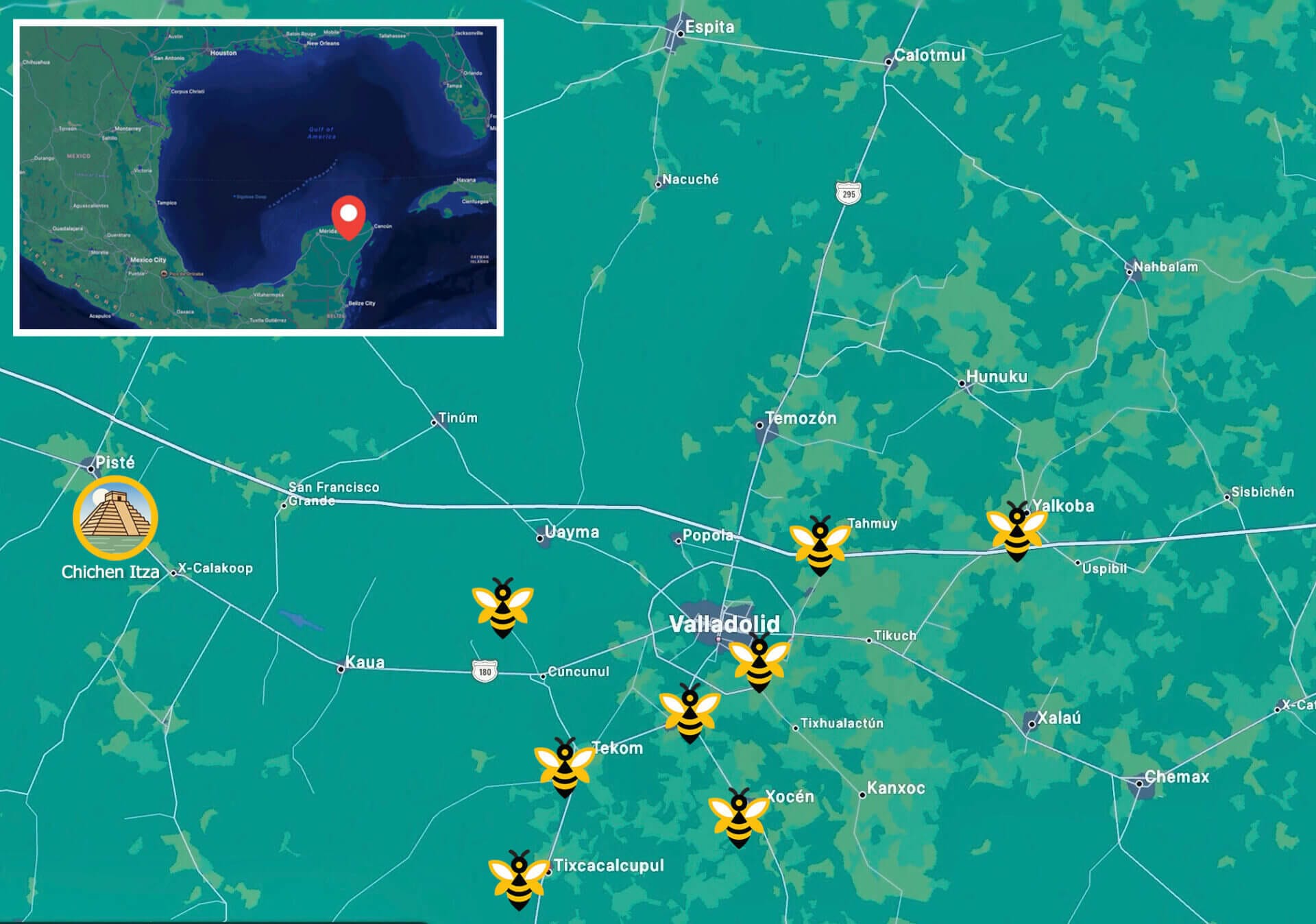

The Mayan Melipona Bee Sanctuary helps support a quiet economic engine which, in turn, supports dozens of rural Maya communities (see map above) and helps preserve time-honored practices through real-world livelihoods. Beekeepers here are increasingly adopting regenerative agricultural techniques, planting native trees to support bee forage, and participating in certification programs that emphasize fair trade and environmental stewardship. In doing so, they are actively shaping a future where ancient knowledge and biodiversity can thrive side by side.

Beekeeping and The Maya Hinterland

The Maya Hinterland refers to a lush, largely undisturbed jungle area nestled between Puerto Morelos and Leona Vicario in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Stretching inland from the Caribbean coast along the Ruta de los Cenotes, this zone comprises dozens of small Maya villages surrounded by dense lowland forest and cenotes, distinctly separate from the developed resorts of the Riviera Maya. It’s in this setting that the Maya Hinterland Project works to preserve Indigenous culture, support melipona beekeepers, and develop educational and environmental initiatives within the region

The Maya Hinterland Project, led by photographer and community advocate Michael A. Maurus, is a grassroots initiative dedicated to empowering Maya communities between Puerto Morelos and Leona Vicario through cultural preservation, education, and sustainable livelihoods. By supporting traditional Melipona beekeepers, facilitating honey distribution, and creating learning spaces like the Maya Theater and free community library, the project strengthens Maya identity and fosters economic resilience.

The initiative encourages sustainable environmental stewardship through its nature reserve sanctuary and guided excursions. Proceeds from Michael’s photography prints and guisded guest visits directly benefit local families and beekeeping enterprises.

Why It All Matters

At a time when pollinator populations are collapsing around the globe, the story of the melipona bee is a reminder that sustainability is not a new concept. It’s ancient. The Maya knew how to live in balance with nature, and that wisdom still echoes in the hives tucked behind modest homes across the peninsula.

Protecting melipona bees means protecting a lineage of Indigenous knowledge and environmental stewardship. Their honey may be rare, but their value is immeasurable. So, next time you taste that golden drop, remember: it’s not just honey—it’s history in a jar.

Educational and cultural centers in and around Valladolid and the Maya Zone of Quintana Roo also play a key role in transmitting bee-related knowledge to younger generations and visitors. Institutions like Xkopek Beekeeping Park offer guided experiences where guests can see melipona hives up close, learn about bee biology, and participate in hands-on workshops. These experiences are not just tourist gimmicks—they’re part of a conscious strategy to promote cultural resilience through ecological education.

Are You Interested in Learning More About Meliponiculture?

If you have the time to plan ahead, I would strongly recommend you reach out the organizers of the Mayan Melipona Bee Sanctuary in Valladolid or Michael Maurus to see if a guided visit can be arranged in the Maya Hinterland near Puerto Morelos. Here is where you will find the most authentic experience without all the touristy hype.

If time is an issue, there are an increasing number of local tour operators who have identified a growing interest in eco and community based tourism and have found a way to incorporate a visit to a meliponario into their excursions. Xcaret and Xel Ha have working meliponarios on their park grounds that they harvest twice annually.

If you are in the Yucatan near Valladolid, you can visit Xkopek, Parque Apícola on your own or as part of a tour. Another option is the Meliponaria Lool Há. Even my favorite boutique hotel, Zentik Project, has their own melipona bee house on site.

On the island of Cozumel, check out the Mayan Bee Sanctuary or visit Bee Friendly as a part of this fun excursion. If you are near Tulum, Choco Cacao Maya in Cobá has a Melipona bee sanctuary that is worth visiting especially when paired with a trip to the ruins and a dip in one of the nearby cenotes.

What Can You Do to Support Melipona Bee Populations?

If you are a local resident living in the Yucatán and Quintana Roo, you are in a unique position to directly support the survival of Melipona beecheii and the cultural heritage tied to meliponiculture. Here are some tangible, region-specific actions you can take:

Plant Native, Flowering Species

Melipona bees rely on diverse, native vegetation for nectar and pollen. Residents can support them by planting pollinator-friendly plants like flor de mayo, xtabentún, ramón, achiote, and local fruit trees. Avoiding non-native ornamental species and choosing plants that flower year-round helps ensure bees have food in both rainy and dry seasons.

Avoid Pesticides and Herbicides

Many rural and even urban residents use agrochemicals for lawns, milpas, and gardens. These substances are toxic to stingless bees, even in small doses. Switching to natural alternatives—or avoiding chemical use altogether—can dramatically improve local bee survival.

Support Local Meliponicultores

Buy melipona honey and bee products (like propolis, balms, or soaps) directly from Maya families or cooperatives in your community or nearby villages. Look for vendors in places like Valladolid, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, José María Morelos, and other areas of the Zona Maya. Ask about their hives, methods, and family history—they’ll often be happy to share their knowledge.

Teach the Next Generation

If you’re a parent or educator, involve children in learning about melipona bees. Visit local farms or bee sanctuaries, or join workshops offered by cooperatives and conservation groups. The more awareness children have, the more likely they are to value and continue the tradition.

Host a Hive

If you have outdoor space and live in a bee-friendly environment, consider working with a meliponiculturist to host a hive on your property. These hives are compact, quiet, and safe—even for children—since Melipona bees don’t sting. Hosting a hive helps provide habitat and can connect you to local traditions in a meaningful way.

Advocate for Forest Protection

Melipona bees thrive in biodiverse ecosystems. Supporting reforestation programs, opposing deforestation for tourism or monoculture, and speaking out in favor of community-managed forests can all help protect critical habitats.

Learn More

Watch this great documentary about the melipona bees. (Spanish with English subtitles – 27 minutes)